Electoral Insight – 2004 General Election

Electoral Insight – January 2005

Women Beneath the Electoral Barrier

Nikki Macdonald

Member, Equal Voice Footnote 1

In the 1980s, due to a variety of circumstances, Canadians witnessed a historic rise in the number of women elected to the Canadian House of Commons. While many of the same circumstances existed throughout the 1990s, there was little change in the membership of the House and therefore little opportunity for additional women to run for office. For the 2004 election, the political landscape in Canada had changed dramatically. Three of the four largest political parties had elected new leaders, two parties had merged to create the new Conservative Party of Canada, and the political finance provisions of the Canada Elections Act had received a complete overhaul. The shift opened up more opportunities for women to run. The critical step, however, was for more women to win the nominations of their parties. Despite the fact that most parties made efforts to identify and recruit more women, women made up only 23% of the nominated candidates of the four major parties. It was not surprising, therefore, that the number of women elected did not significantly increase.

Major progress in the 1980s

| 1980 | 1984 | 1988 | 1993 | 1997 | 2000 | 2004 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | 10 | 5 | 13 | 36 | 37 | 39 | 34 |

| Progressive Conservative | 2 | 19 | 21 | 1 | 2 | 1 | n/a |

| Reform/Canadian Alliance | n/a | n/a | n/a | 7 | 4 | 7 | n/a |

| Bloc Québécois | n/a | n/a | n/a | 8 | 11 | 10 | 14 |

| N.D.P. | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 5 |

| Conservative* | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 12 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Totals | 14 | 27 | 39 | 53 | 62 | 62 | 65 |

* Conservative refers to the new Conservative Party of Canada created in 2003 by the union of the former Canadian Alliance and Progressive Conservative parties.

Information: Parliament of Canada

In the 1980 federal election, only 14 women were elected to the House of Commons, making up just 5% of the membership. By the close of that decade, the number of women elected had almost tripled to 39, or 13.2% of the 295 members of Parliament. Footnote 2 Several reasons were given to explain this large increase in the number of women elected. First, women had made inroads into the traditional recruitment grounds for candidates. Improved social and economic status meant that there were more women in law, business and local politics. Secondly, women inside and outside the parties were demanding better representation. Thirdly, changes to the election financing rules at the federal level helped to break down some of the traditional barriers for women candidates. And finally, there was a relatively high rate of turnover among members of Parliament, which meant that there were more opportunities for women to be elected. Footnote 3 In the next decade, many of the same conditions applied, except for the important difference that there was little turnover in the membership of the House during the next three elections and therefore fewer opportunities arose to elect additional women.

Progress in the 1990s stalls

In 1993, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien's Liberals won with a large majority and the number of women elected to the House of Commons increased to 53, or 18% of the 295 members of Parliament. Footnote 4 Mr. Chrétien used his prerogative to appoint candidates to meet his stated goal of having women make up 25% of the Liberal candidates. Footnote 5 In the federal elections of 1997 and 2000, the Liberals would go on to form two additional majority governments. The three majority governments created a decade of stability in the House of Commons and there was a much lower rate of turnover among members. Furthermore, Mr. Chrétien followed a general practice of protecting the nominations of Liberal incumbents, which further reduced the rate of turnover. The effect of the low turnover was evident between the 1997 and 2000 elections, when there was no change in the number of women elected. In both elections, 62 women were elected to the House of Commons, making up 20% of its members. The opportunity to increase the number of women elected appeared to have opened up in 2004, when the political landscape had changed significantly.

Toward the 2004 election

By the call of the 2004 federal election, there were three new leaders among the major parties, a new political party, new political finance provisions and a significant turnover in members. The previous year had seen the retirement of two political leaders who had served throughout the 1990s. Alexa McDonough retired as leader of the New Democratic Party and, for the first time in over a decade, a man, Jack Layton, was elected to lead the party. Jean Chrétien retired as both prime minister and leader of the Liberal party, and was replaced by Paul Martin. The Canadian Alliance and Progressive Conservative parties united under a new banner to form the Conservative party. Former Alliance leader Stephen Harper was elected to lead the new united party. Only Gilles Duceppe, leader of the Bloc Québécois, had previously led his political party through a federal election. Many members of Parliament who had served through the 1990s made the decision to retire, thereby opening up ridings to the nomination of new candidates. Footnote 6 In addition, Paul Martin decided not to follow his predecessor's practice of protecting the nominations of incumbents, which opened up further opportunities within the Liberal party for a competitive nomination process. The new political finance provisions, which had been adopted by Parliament in 2003, included contribution limits for individuals, corporations and unions, and spending limits for nomination contestants, thereby reducing a key barrier for women, the ability to raise funds for an electoral campaign.

Along with this significant movement in the political leadership and landscape, women continued to make social and economic gains that positioned them for possible recruitment as candidates. It remained to be seen how the parties and, in particular, the party leaders would respond to the challenge to elect more women. Equal Voice, a multipartisan advocacy organization devoted to promoting women's participation in Canadian politics, challenged all party leaders to take action to increase the number of women elected to the House of Commons. Specifically, Equal Voice had set a goal of 104 women members in 2004. This goal is premised on the belief that women need to make up approximately one third of the members of the House of Commons, if they are to have a significant and lasting impact on its proceedings. Footnote 7

The support of the party leaders is critical to ensuring that more women will be nominated and subsequently elected to the House of Commons. In Canada, political parties are the key actors in the electoral process. Specifically, political parties recruit and nominate candidates for elected office through local riding associations. Footnote 8 While the parties may differ in the degree to which the selection of candidates is left to the local riding association, the party apparatus is critical to the nomination process. Party leaders, in particular, can ensure that the party apparatus is open to recruiting and nominating more women. In the lead-up to the federal election of 2004, each of the four major parties took a different approach to the recruitment of women, which led to varying degrees of success in nominating them for election.

The 2004 election

Dr. Ruby Dhalla (Liberal), who won the Brampton–Springdale (Ontario) riding, became the first Sikh woman member of Canada’s House of Commons

In 2003, while running for the leadership of the Liberal party, Paul Martin declared that he would undertake to increase the number of women candidates and to do so in "winnable ridings" through active recruitment for nominations; and if that did not work, to use his power to appoint candidates. Footnote 9 He stated that his goal was to ensure that Liberal members and, indeed, the House of Commons were representative of the population at large and that he would like to see women make up 50% of the elected members. Footnote 10 However, as the nomination process got underway, he also stated that he would not involve himself in the local affairs of riding associations. Moreover, he discontinued the practice of protecting the nominations of incumbents, thus opening up ridings for a competitive process. Footnote 11

The Liberals ended up nominating 75 women for election. This represented 24% of the full slate of 308 candidates that they fielded across Canada. Footnote 12 While the candidate selection process had identified many more women who had both the interest and background to run, these women were not successful in winning the nominations. The party had an informal mentoring system that paired potential female nominees with successful women members. However, that was not enough to help women win more riding nominations. Footnote 13 In previous elections, the Liberals had nominated an equal number of women, but then Liberal leader Jean Chrétien had used his prerogative of appointing candidates to reach 25%. In 2004, Paul Martin did not use his prerogative to specifically appoint more women as candidates. Instead, he used that prerogative primarily to appoint several high-profile candidates, most of whom were male. Footnote 14 It is possible that if Paul Martin had appointed more women candidates, more women would have been elected. As it is, 34 out of 135 Liberal members elected, or 25% of their caucus, are women. Footnote 15

Audrey McLaughlin est devenue la première femme chef d’un parti politique fédéral au congrès à la direction du N.P.D. tenu en 1989 à Winnipeg.

The New Democratic Party also had a new leader in the 2004 federal election. What was highly significant, not only for the party but also for federal politics, is that for the first time in 15 years, the N.D.P. was not led by a woman. Since 1989, when Audrey McLaughlin was elected leader of the N.D.P., followed by Alexa McDonough in 1995, the N.D.P. had provided female leadership in federal politics. The symbolic benefit of a female political leader for all women seeking federal office is significant. Not only does it demonstrate to potential female candidates that they can succeed and even lead in the federal political process, it also informs the political culture that women are capable of being elected. It helps to break down the psychological and cultural barriers that have traditionally limited women's involvement in politics. Footnote 16

N.D.P. leader Jack Layton continued his party's practice of a formal affirmative action program. Initiated many years ago, the N.D.P. policy was to freeze nominations until the local riding association could demonstrate that a woman or another member of an under-represented group was in the running for nomination. Footnote 17 Time, education and awareness have enabled this policy to ensure that women and other minorities are promoted for nomination. Footnote 18 However, despite the formality of their recruitment, some N.D.P. women still faced difficulty in winning a nomination. In 2004, several high-profile women found themselves unprepared to manage the competitiveness of the nomination process successfully and they either lost or dropped out before the race began. Footnote 19

The result was that 96 of the N.D.P. candidates (31%) were women. Footnote 20 Of the 19 members of Parliament elected from the N.D.P., 5 are women, representing 26% of the party's membership in the House. Footnote 21

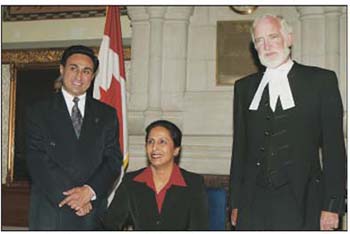

The first husband-wife team elected to the House of Commons arrived when Nina Grewal (Fleetwood–Port Kells) joined her husband Gurmant (Newton–North Delta), who was first elected in 1997. On July 15, 2004, the two British Columbia Conservatives took the oath of office with Clerk of the House William Corbett (right).

Conservative Party leader Stephen Harper shared with party leaders Paul Martin and Jack Layton the challenge of running his first federal election as leader, but he had the added task of introducing a new party to the electoral scene. The new party combined different views when it came to the representation of women. On the one hand, the former Progressive Conservative party had put in place certain measures aimed at encouraging women to become candidates – for example, the Ellen Fairclough fund. It had also elected Canada's first and only female prime minister, the Right Honourable Kim Campbell. The former Canadian Alliance party, on the other hand, like its predecessor the Reform party, had always rejected affirmative action measures to encourage the nomination of women candidates. Footnote 22 Thus, when asked by Equal Voice what action he would take to promote the nomination of women, leader Stephen Harper replied that he would leave it to the local riding associations. Furthermore, he noted that women in his party were successful due to their own hard work. Footnote 23 In the end, only 36 of the Conservative Party's 308 candidates (12%) were women, Footnote 24 while 12 of the 99 members elected from the Conservative Party are women. Footnote 25

Campaign signs in Laval, Quebec.

Of the four party leaders discussed here, only the Bloc Québécois' Gilles Duceppe had previously led his party in a federal election. The party, which runs candidates only in the province of Quebec, has demonstrated a commitment to nominating women. Beginning in 2003, the party actively sought to identify and recruit women for nomination. However, as experienced by the other parties, some of these women dropped out or failed to win nominations. Footnote 26 In 2004, 18 of the 75 Bloc candidates (24%) were women, a proportion that is slightly lower than among the Liberals and the N.D.P., which fielded candidates in all 308 ridings across Canada. Footnote 27 The election resulted in 14 women winning seats as part of the Bloc's 54-member caucus (or 26% of the total). Footnote 28

Conclusion

Together, the nomination processes of the four major parties led to 225 women being nominated out of a total of 999 candidates, or approximately 23%. The final electoral result was therefore predictable – only 21% of the members elected to the House of Commons in 2004 are women. Footnote 29 This is not a significant increase over the elections of 1997 and 2000, when women made up 20% of the elected members. The conditions that had been evident during the near tripling of the representation of women in the House of Commons in the 1980s still existed in 2004 and included changes in party leadership, the creation of a new party, the increased turnover of members and improved election financing rules. The Liberals, the N.D.P. and the Bloc all had formal and informal mechanisms to identify and recruit potential women candidates, but the number of women nominated to run for elected office did not increase. It is evident, therefore, that women need additional support to compete for and obtain nominations. Party leaders are well positioned to provide that additional support, whether through changes to the party's nomination process or by directly appointing candidates. The election of 2004 demonstrated that for women to make the breakthrough to that significant one third of the elected members of the House, commitment and determination from the party leaders, the party apparatus and women themselves will be required.

Notes

Return to source of Footnote 1 Nikki Macdonald provided electoral research for Equal Voice during the 2004 general election. Equal Voice is a multi-partisan advocacy organization that promotes the involvement of women in politics.

Return to source of Footnote 2 Women Candidates in General Elections – 1921 to Date, Parliament of Canada Web site: www.parl.gc.ca.

Return to source of Footnote 3 Linda Trimble and Jane Arscott, Still Counting: Women in Politics Across Canada (Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2003), pp. 46–48.

Return to source of Footnote 4 Parliament of Canada Web site.

Return to source of Footnote 5 Sydney Sharpe, The Gilded Ghetto: Women and Political Power in Canada, 1st ed. (Toronto: HarperCollins Publishing Ltd., 1994), p. 173.

Return to source of Footnote 6 In 2004, 54 members chose not to seek re-election, in contrast with 2000, when 22 members chose not to seek re-election. Source: Electoral History, Parliament of Canada Web site.

Return to source of Footnote 7 See Equal Voice Web site, www.equalvoice.ca. Note: While the phrase "104 in 2004" made a catchy goal to communicate, it was premised on the desire to move closer towards one-third representation in the House. It has been noted that women need to make up 30% of the House of Commons to have a major, sustained influence (Sharpe, The Gilded Ghetto, p. 218).

Return to source of Footnote 8 Richard J. Van Loon and Michael S. Whittington, The Canadian Political System: Environment, Structure and Process, 3rd ed. (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1981), pp. 304–325.

Return to source of Footnote 9 June 14, 2003, National Liberal Party Leadership Debate, televised.

Return to source of Footnote 10 Paul Martin's speech to National Women's Liberal Commission, National Liberal Leadership Convention, November 2003.

Return to source of Footnote 11 Brian Laghi and Campbell Clark, "Copps's Battle a Symptom of Liberal Infighting," The Globe and Mail, January 17, 2004, p. A11.

Return to source of Footnote 12 Numbers provided by Liberal Party of Canada to Nikki Macdonald as part of research for Equal Voice, posted on www.equalvoice.ca.

Return to source of Footnote 13 Chair of Liberal Women's Caucus, Anita Neville, MP, in discussion with Nikki Macdonald, May and July 2004.

Return to source of Footnote 14 Refers to Paul Martin's appointment of several British Columbia candidates, including Ujjal Dosanjh, former N.D.P. premier of B.C., and David Emerson, formerly of Canfor, a forest products company based in Vancouver.

Return to source of Footnote 15 Party Standings, 2004, Parliament of Canada Web site.

Return to source of Footnote 16 For a discussion of the challenges women party leaders have faced in Canada, see Trimble and Arscott, pp. 69–99.

Return to source of Footnote 17 Reply of Jack Layton, N.D.P. leader, to Rosemary Speirs, Chair of Equal Voice, March 25, 2004. Posted on www.equalvoice.ca.

Return to source of Footnote 18 Nikki Macdonald in conversation with Judy Wasylycia-Leis, N.D.P. member of Parliament, April 29, 2004.

Return to source of Footnote 19 In conversation, Judy Wasylycia-Leis gave the example of Mary Woo-Sims, former B.C. ombudsman, who was defeated by Ian Waddell for the N.D.P. nomination in Vancouver Kingsway.

Return to source of Footnote 20 Numbers provided to Nikki Macdonald by the New Democratic Party. Posted on www.equalvoice.ca.

Return to source of Footnote 21 Party Standings 2004, Parliament of Canada.

Return to source of Footnote 22 For a useful discussion of the Reform/Canadian Alliance approach, see Lisa Young, "Representation of Women in the New Canadian Party System", especially pages 191–196, in William Cross, ed., Political Parties, Representation, and Electoral Democracy in Canada (Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press, 2002).

Return to source of Footnote 23 Reply of Stephen Harper, leader of Conservative Party, to Rosemary Speirs, Chair of Equal Voice, March 29, 2004, posted on www.equalvoice.ca.

Return to source of Footnote 24 Numbers provided to Nikki Macdonald by Conservative Party of Canada. Posted on www.equalvoice.ca.

Return to source of Footnote 25 Party Standings, Parliament of Canada.

Return to source of Footnote 26 Claude Potvin, official Bloc spokesperson, in conversation with Nikki Macdonald, June 23, 2004.

Return to source of Footnote 27 Numbers provided by Bloc Québécois to Nikki Macdonald. Posted on www.equalvoice.ca.

Return to source of Footnote 28 Party Standings, Parliament of Canada.

Return to source of Footnote 29 Party Standings, Parliament of Canada.

Note:

The opinions expressed are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect those of the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada.